The Cold War today is frequently seen as an overreaction. This is what many people—even those who lived through it—believe. It is certainly what I was taught in school. I remember, however, a dramatic argument with my father while I was in college. I told him that the Cold War was just an unnecessary distraction. My father, banging his fists in the air, declared, “You are learning from too many liberals! I was in the Navy, I know it was a real threat!” I dismissed him.

Delving into history for the development and writing of Crown Colony of Spies, and specifically having to get into the minds of characters on the front lines, I came to see my father’s point. Much of our collective history resides in the seemingly pointless and overly drawn out Vietnam War. I do not disagree with the tragedy of this war. I do not disagree that at times the policies and reactions were ridiculous in hindsight—perhaps the result of the collective social post-traumatic stress from World War Two and the Korean War, wars which most policy makers experienced directly. The Cold War was, however, a real threat. It is hard for us when we look at the frenzy of anti-Communism, especially the McCarthy period, to understand why it happened. If we don’t understand, however, we run the risk of repeating history.

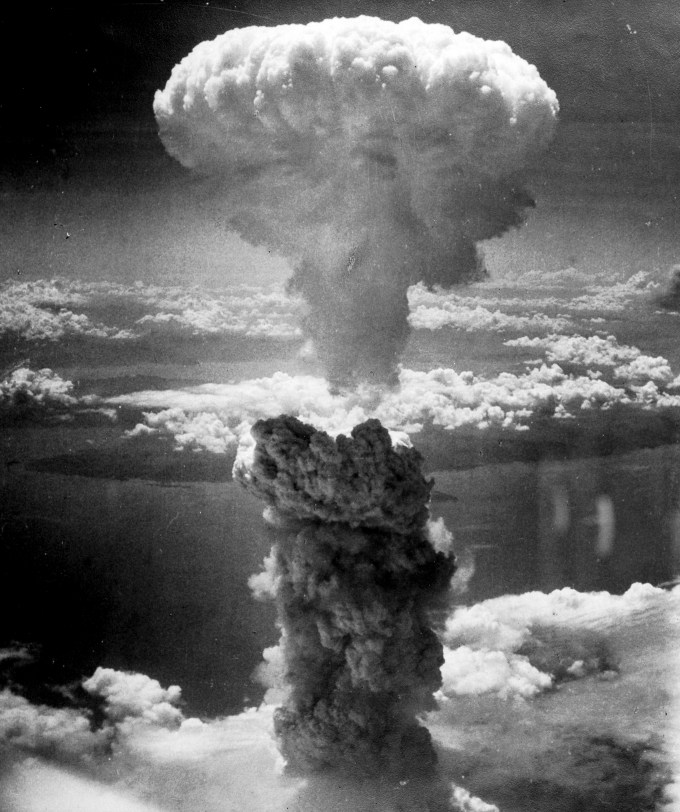

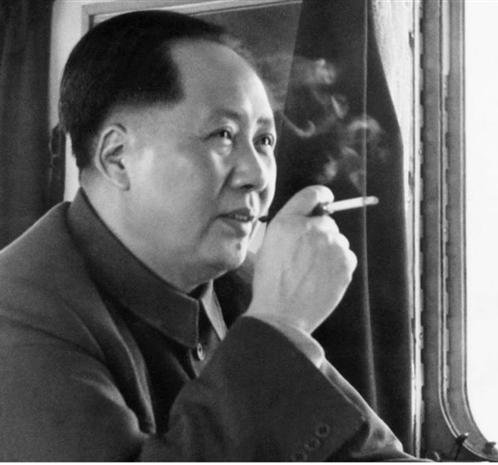

Let’s take a look at the major Communist regimes at the time, the Soviet Union and China. Both were guilty of genocides of their own people—genocides several times greater than the loss of life in German concentration camps. In China, an estimated forty million people died between 1959 and 1963 in the Great Famine (otherwise known as the Great Leap Forward). This famine was intentionally produced by Mao, who literally robbed his people of food to a point where the average caloric intake in China was less than the average caloric intake at Auschwitz. He did so in order to sell food overseas and generate capital to build up the Chinese military, and specifically to build an atomic bomb, which he accomplished in 1964. Using the same method, Stalin was responsible for some seven million deaths in a single year (1932-1933). Comparing this death rate with the much better-known Holocaust, when six million Jews were exterminated over a nine-year period, we can get a sense of the monstrous scale of horror we are talking about. Both these regimes practiced systematic slaughter of political dissidents and a long list of others. And the list of atrocities goes on. Is it any wonder that as these regimes developed weapons of mass destruction that they were seen as a terrifying threat? Is it any wonder that the U.S. didn’t want that coming to our country?

I’d like to focus my discussion on the time period from 1956-1959, when Crown Colony of Spies takes place. This is post McCarthyism and represents a bridge between the Korean and Vietnam wars. When I approached a Stanford history professor about this period in China, he replied, “Why are you interested in that period in Asia. Nothing was going on.” To me, however, much was going on. Especially in Asia. The events in this time period would lead Eisenhower to enter the Vietnamese conflict, and to encourage Kennedy, before he even came into office, to expand U.S. involvement there.

In early 1956 Khrushchev publicly denounced Stalin. This led to a brief period of open public discourse, which was mirrored by Mao’s Hundred Flowers Campaign. In both countries, however, these policies came crashing down with harsh repercussions for those who voiced their opinions. In the case of Khrushchev, his denunciation of Stalin lead to a backlash from his fellow party members, which almost resulted in his overthrow. He had to reestablish aggressive policies in order to maintain power, which resulted in several Soviet occupations of Eastern Europe later that year.

In October 1956, the Soviets invaded Hungary. This was not just a minor occupation. This was a fully drawn out bloodbath of a war, which had been preceded by an occupation of Poland and the violent suppression of anti-communist protests in Prague and the Republic of Georgia. It was deja vu of the beginnings of World War Two. The world, however, failed to respond to Hungary’s pleas for help.

Only a few days before, the British and the French had invaded Egypt in order to reclaim the Suez Canal, which Egyptian President Nasser had recently

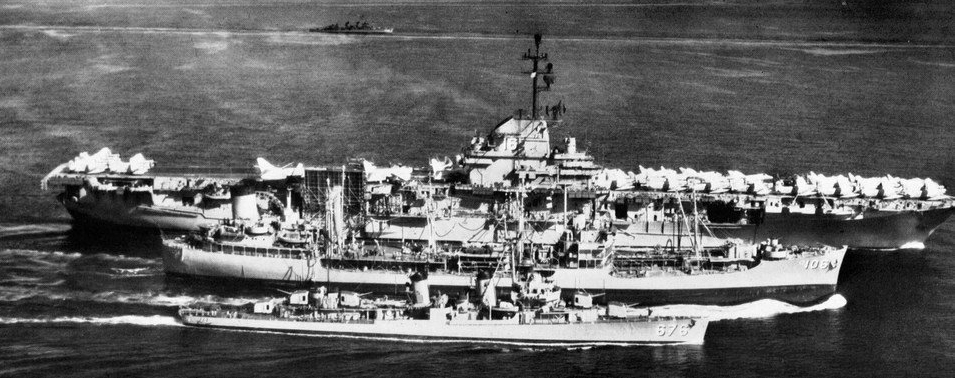

nationalized. The Suez Canal represented the main artery in shipping between Europe and Asia. Its seizure represented a direct threat to the Western economy. The Soviet Union, who supported Nasser, threatened world war in response to the attack. Making matters particularly complicated, the British and French invaded Egypt to the utter surprise of President Eisenhower. Both countries had been negotiating along with the U.S. for peace in the Middle East and both countries were publicly jockeying for it in the U.N. All the while they had been building the largest naval fleet seen in the Mediterranean since World War Two.

This subterfuge was an ultimate betrayal to the U.S. and severely damaged Anglo-American relations for some time. Eisenhower believed—and for good reason—that the world was on the brink of war; to interfere in the Hungarian Revolution would put U.S. and Soviet troops head to head, which especially considering the concurrent Suez Canal situation, would make world war an almost certainty.

Despite that Eisenhower’s decision potentially averted a world war, he agonized over the neglect of Hungary in 1956. As a result, he created the Eisenhower Doctrine in 1957, which stated that any aggression by Communists against a sovereign nation would result with U.S. military intervention. This doctrine would be the ideological foundation for U.S. involvement overseas for the rest of the Cold War, including the Vietnam War.

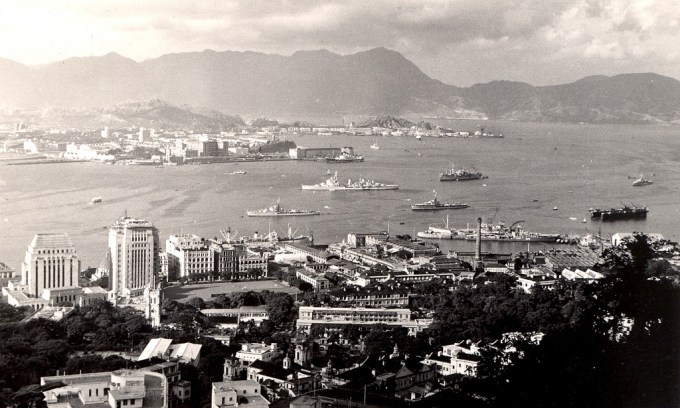

Anglo-American relations were meanwhile further stressed due to one little city in Asia, the British Colony of Hong Kong. At the time, the economy in Britain was sour, still burdened by debts from World War Two. The value of the pound was largely held up by the bustling, growing, manufacturing based economy of Hong Kong; Britain needed to protect it at all costs. The biggest threat was China, but not so much that they would invade, but that China would cut supply and water routes to Hong Kong or cause other disturbances which would impact the economy. When riots broke out in Hong Kong in 1956 between Communist and Nationalist supporters, China specifically threatened to retaliate should another such riot occur. So, the British sided with the Communist Chinese in foreign policy at the U.N. The U.S. did not even officially recognize Communist China at the time, let alone support them on anything. The riff between the U.S. and Britain over this issue was so great that the U.S. threatened a trade embargo against them.

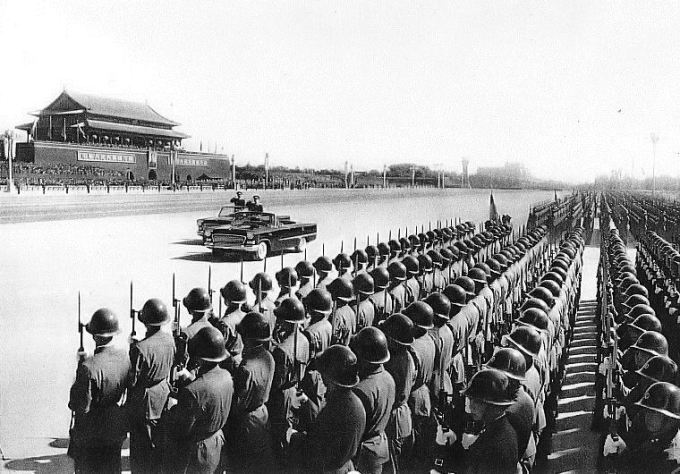

China was, of course, perceived to be an ally of the Soviet Union. China, with the largest army in the world and with a leader who publicly had no issues massacring half his population in war just to win, had plenty of manpower to destroy and invade. Though they were significantly technologically impaired, an allied axis with the Soviet Union, which was believed at the time to have arms capabilities greater than the U.S., could lead to an extensive war. To make the perceived threat greater, the Chinese had fought alongside the North Koreans in the Korean War. Though behind closed doors the relationship between the Soviet Union and China was deteriorating, that was unknown at the time to the U.S. The military capabilities of China were also not clear to the Western powers, making China one of the greatest targets for intelligence gathering in the world.

In this time period, Communism was spreading throughout Asia. Riots similar to those in Hong Kong broke out almost concurrently in Singapore. Communist guerilla uprisings broke out in Indonesia, Laos, Burma, Malaya (present day Malaysia) and North Vietnam. In Taiwan there were anti-American riots. To the U.S., the spread of Communism through Asia, with a perceived allegiance between China and the Soviet Union, coupled with the Soviet’s active invasion of countries in eastern Europe, was closely monitored and understandably was perceived as a threat. In 1958, China started shelling Taiwan in the second Taiwan Missile Crisis, the first being only a few years earlier in 1955. This event, which resulted with the then largest armada in history, involved active discussions behind closed doors in the White House of dropping an atomic bomb on China.

Hong Kong, on the edge of China, was a valuable strategic location for espionage. In fact, the largest U.S. Consulate in the world, filled with intelligence officers, was in Hong Kong. Even if the threat of an invasion was not a daily one to civilians there, to those who worked in that world, the threat of the spread of Communism and the possibility of world war was palpable. Espionage was practically an industry of its own in Hong Kong. This is why I set my story there.

Throughout Crown Colony of Spies appear actual quotes from world leaders and newspapers of the time. You can read for yourself the bellicose rhetoric and feel, perhaps, why those in policy and intelligence understood the threat of Communism and world war to be real. You may be able to draw some similarities of what was happening then to what is happening in the world today.

For reference, and for your own further reading, I have provided a select bibliography on this site.